Above, further to my previous post (Five Wurst, Kebab, and Noodle Stands, the 10th District, Vienna): A photo of one more Viennese snack stand, Kebab Mann’s Crazy Noodels (sic), taken on the Quellenstrasse in the 10th district on a wintry afternoon a year or so ago. I am posting the photo not only for its bold misspelling of “noodels” (puzzlingly modified by the adjective “crazy”) or for its logo (a portrait, aptly captioned “Kebab Mann,” of Kebab Mann himself, dressed in his own Kebab Mann t-shirt and flanked by a large döner kebab) but also for the over-the-top diversity and eccentric orthography of its menu: Faux-Asian “nudel” (noodle; note the singular), Turkish-inspired”kebab” (properly spelled!), “dürüm” (Turkish-style sandwich of grilled meat wrapped in thin flatbread; note the singular again), German “mann” instead of “man,” and one-hundred-percent-American “hotdog” (again, note the singular). These offerings are augmented by “mais” (corn) and “langosch,” a German phonetic spelling of làngos, Hungarian fried flatbread, the latter lending a faintly nostalgic reminder of the bemoaned Hapsburg Empire. If my memory serves me right, Kebab Mann’s Crazy Noodels now stands derelict, but whether despite or because of its menu, I’m not sure.

Street Commerce

Monumental Impermanence: Five Wurst, Kebab, and Noodle Stands, the 10th District, Vienna

Five fast-food “boxes” in Favoriten, the 10th district of Vienna. A (somewhat lengthy) bit of background plus a few reflections — mostly factual but partly speculative — on the content of the photos follows the last of the four images below.

Background

In Vienna, during the 19th-century, wandering vendors sold cooked sausages from baskets and from portable bins — low-cost fast-food for time-pressed workers, many having no cooking facilities in their rented rooms and over-crowded apartments.

By the early-20th century, wheeled sausage carts appeared on the streets Vienna. From the 1960s on, semi-permanent kiosks — würstelstände — took root on the city’s sidewalks and street corners, serving food and drink and providing places to linger and gather — cafe-restaurants, as it were, for people with the shortest of lunch breaks, the thinnest of pocketbooks, the most work-soiled hands and clothes, and the strongest of appetites. As the decades passed, Vienna’s sidewalk würstelstände increased in size, variety, and numbers, and their menus evolved to reflect waves of demographic change.

Today, the backbone of würstelstände offerings remains “traditional” sausages, their origins grounded in the tastes of 19th-century economic migrants to Vienna from the one-time expanses of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire: Germanic white and frankfurter sausages, Polish kielbasa, Slovenian meat- and cheese-filled sausages, and paprika-laden sausages of putative Hungarian origin. In recent decades, however, such “traditional” sausages yielded counter-space to fast-food dishes descended from the cuisine of more recent economic migrants from Anatolia, the Balkans, and the Middle East, as well as to Austrian oversimplifications of Asian cuisine. The results have shaped new “traditions” that challenge the imagination and, more painfully, the digestive capabilities of all but the hardiest diners. Not least, the offerings, menus, and signage of the present generation of Viennese würstelstände have also brought about linguistic transformations that compromise the integrity of German, Turkish, and other languages.

Each of the five kiosks portrayed in this post expounds on this tale. All are located along a short stretch of Quellenstrasse in Favoriten, Vienna’s 10th district. From the late-19th-century until the Second World War, Favoriten was a district of factories, brick and tile works, garden farms, and craftsman’s ateliers, and the home of people who worked in and around them. At the start of the 20th-century, the distinctly working-class population of Favoriten comprised large numbers of descendants of emigre Bohemians and Moravians as well as other groups including more than 8,000 Jews, many originally from Hapsburg Galicia. (Favoriten’s immense synagogue, destroyed by arson during the Kristallnacht pogrom of November, 1938, was one of Vienna’s largest and dominated the neighborhood’s skyline). By the middle of the 20th century, the district’s Bohemian and Moravian population had folded into mainstream Vienna, and the Jews of Favoriten had been segregated, terrorized, deported, and murdered by and at the behest of Nazi Germany, of which Austria formed an integral part from 1938-1945.

In the final days of World War II, a large portion of Favoriten’s industrial and housing stock was destroyed by aerial and artillery bombardment followed by house-to-house combat. A massive rebuilding program began in the 1950s. By the 1960s, an exodus of long-time residents from Favoriten to more attractive housing estates and, eventually for some, to more upscale suburban quarters, made room for new arrivals. The first to settle were Turkish “guest workers” followed by their families and then by subsequent waves of Anatolian immigrants. During the decades straddling the turn of the present century, Turks were followed by Serbs, then Bosnians, and, in more recent years, by Chechens, Afghans, Iraqis, and other peoples fleeing places of conflict.

Thoughts on the stands portrayed

The signage of Evin Imbiss, portrayed in the first photo above, is a study in multi-cultural amalgamation. Evin is Turkish for “Your House” and Imbiss a German word for snacks and, later, for snack-bar. A click on the photo will enlarge it, revealing a menu guaranteed to deter all but the hungriest adolescents and low-budget diners with a penchant for the tortures of culinary post-modernism. For a half-century now, newly arrived foreigners in Western Europe have been badgered and oft-times harassed to “integrate.” In its name, offerings, and even its yellow decorative highlights (which seem to blend with the yellow of the building behind it and with the logo on the phone-both at the left of the frame), Evin Imbiss provides an apt, albeit unintended, symbol of a merger of identities.

The stand portrayed in the second photo, Würstel Box, bears a straight-forward, more Germanic, generic name: Würstel being the diminutive of Wurst and Box an anglicism for kiosk. The regular clientele of Würstel Box, however, consists of an uninterrupted day- and night-time stream of boisterous and moderately antisocial high-volume beer drinkers drawn from nearly as many nationalities as now populate the district.

Tiger’s Box, portrayed in the third photo, with its wonderful slogan, Tierisch Gut! (“Beastly Good!”), sells takeaway noodle dishes, bland Austro-Anatolian re-imaginings of Asian mainstays. Note the black-lettered text on the left side of Tiger’s Box, partly obscured by the stand’s half-lowered louvered protective gate. The full text, a vestige of the days when the very same stand sold döner kebab (nb. Middle Eastern shoarma, Greek gyros) reads: “Kebap Essen, Probleme Vergessen,” in English: “Eat kebab, forget your problems” — a straight-forward spiritual prescription of sufficient wisdom and simplicity to warrant adoption as a mantra.

“Kebap Essen, Probleme Vergessen” also reveals a linguistic shift made by the word Kebap, a phonetic spelling of kebab, a Turkish catch-all word for roasted or grilled, cubed, sliced, or ground, and sometimes skewered, meat dishes. At Viennese street kiosks such kebabs are served in bread, Middle Eastern, Turkish, or traditionally Viennese. As a result, kebap transitioned from signifying meat dishes to meaning meat sandwiches, and then to meaning sandwiches in general. Going one step further, kebap made a third leap to mean snacks in general. As evidence, note the sign at the far right of the photo: “Kebap Haus,” underscored by its very non-kebab menu: Pizza, Schnitzel, Fisch, and, as an afterthought, Felafel.

The facade of the stand in the fourth photo has an elegant contemporary finish but the modestly small print of the menu stenciled on its display window mirrors the standard neighborhood fare visible in its interior: i.e. pizza and döner.

The stand in the fifth photo takes the word kebap a quantum leap further on a trajectory from its eastern and carnivore roots westward and vegetarian-wards via the somewhat contradictory offering of Gemüse Kebap, i.e. Vegetable Kebab. Not surprisingly, the display window on the other side of the kiosk, not visible in the photo, betrayed an immense, slowly-turning, very non-vegetarian döner kebab.

Photographic note

All five photos were taken with with a dated and increasingly malfunctioning Fuji X100 digital camera augmented with “50mm-equivalent,” screw-on “tele” converter. I’ve also taken a few photographs of the stands on medium format film; depending on the results, I’ll consider posting a few examples following long-overdue processing and scanning.

Reconsideration: Eye to Eye, Squint to Squint, and Thoughts on Who is Photographing Whom

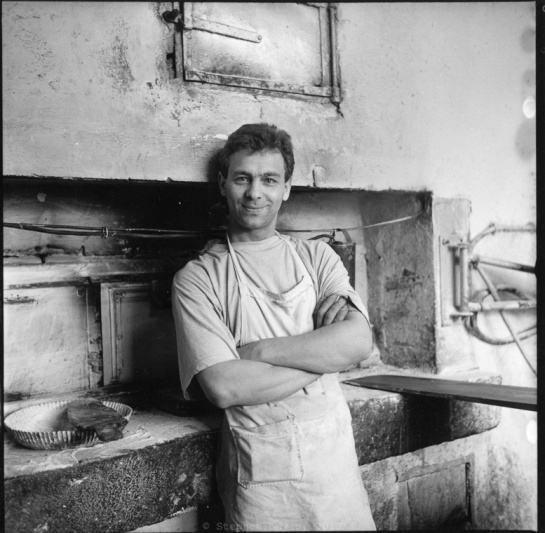

Paint stall workers, Perşembe Pazarı (the Thursday Market), Galata, Istanbul, 2013; B/W negative; Rolleiflex Xenotar f2.8. Click on image to enlarge.

I have not posted to this site since mid-year 2015. Conceptually, long-form reading (for research and for its own sake) led me to push short-form writing to the side. On the visual side, malfunctioning of my supposedly trustworthy digital camera, the increasingly complex logistics of purchasing and processing film, and a search for new photographic approaches and subject matter caused me to reconsider the worth of my backlog of images and of the platforms I’ve used for sharing them. But now, for the moment at least, I’ve decided to pick up the thread …

The connection

The photo above provides continuity to my last post to this site. The photo was taken in the Perşembe Pazarı (Thursday Market) — the centuries-old (millennia-old, actually!) ships’ chandlers and metal-working market at the mouth of the Golden Horn, on the waterfront of the old Galata neighborhood of Istanbul — in one of the narrow streets just behind the buildings fronting the water at the left of the panaromic photo of the waterfront featured in my last post. The street in question contains the stalls and enclosed shops of paint merchants, competitors grouped one after the next as per the guild-like arrangements of traditional markets. The paint merchants test and display custom-mixed colors by dabbing pointillist brush strokes and Jackson-Pollack-like spray bursts onto exposed retaining walls in the increasing number of vacant lots that scar the neighborhood as developers race to position themselves for the windfalls of inevitable gentrification. (For a waterfront street-scape taken elsewhere in Perşembe Pazarı click here.)

Eyes to eyes, squints to squints

For years, I have shied away from candid photography, especially (per my lifelong contrived contrariness to fashions of the moment) the recent rage for “street photography.” To me, hidden cameras and surreptitious photographers can too easily cross the line into cowardliness, trickery, and exploitation. My take is (or maybe was) that achievement of direct eye-contact shows recognition and attentiveness on the part of the photographer towards the person-hood of the subject. Eye contact enables the subject to manifest him- or herself in a manner either inherent to themselves or to themselves as they wish to be at the moment. In short, it leads to willful collaboration of subject and photographer.

Objectivity or self-deception?

Recently, I’ve begun to question my stance. I ask myself how much the achievement of eye-contact and the seduction involved therein are true techniques of environmental portraiture versus how much they might engender projection, surrogate self-portraiture, and/or transcendence of loneliness on the part of the photographer. More abstractly, I wonder whether whether eye-contact is a means for capturing projection rather than subject? Or, more banal, how much the search for eye contact is a but a hangover from, and a nostalgia for, the family snapshots of my childhood?

As to what spurred my questioning … several things:

1. The suggestion of Austrian sociologist Marietta Mayrhofer-Deak, a collaborator on a proposed project, that I reread Photography and Sociology, a 1970s essay by Howard Becker, the octogenarian sociologist, one-time jazz musician, and innovator in participant research into “deviant” behaviors, beginning with one of the first detailed participant studies of marijuana-smokers!

2. A second suggestion from Marietta that I re-examine the detached and clinical, but nonetheless telling and powerfully moving, portraiture of August Sander (the full collection of which can seen on the website of the Museum of Modern Art in New York; and

3. My recent perusal of photos of a series of analogue photos of architectural details — balconies, doors, windows, caryatids, stairways — that I took in Sofia, Bulgaria during a winter of political upheaval and economic collapse nineteen years ago. How much, I now ask myself, did the Sofia series actually portray its inanimate subject matter? How much did my choice of subject matter, viewpoint, and framing actually represent the grim pessimism and insecurity of the society at the time? Or, how much were the photos expressions of my own inner state and preoccupations, independent of subject matter and context? Did the photos tell larger tales of the objects portrayed, their contexts, and the times, or merely express the narcissism or autism of me, the photographer?

More on this — and a sampling of photographs from the series referred to — in subsequent posts.

(Disclaimer: I have not worked or resided in Istanbul since January, 2015. Since then, I have only returned to Istanbul for a two-week stay during which I did not visit Perşembe Pazarı. Thus, I do not know how much of the market area has been razed since nor have I attended to my usual practice of trying to return to provide the subjects of photos with prints of their own, regardless of intervening time. Anyone more up-to-date on the present state of Perşembe Pazarı is welcome to comment)

Shabla, Bulgaria: Seawards and Kitchenwards

The infrastructure of local, coastal fisheries: Boats, boat-launching rails, and fishermen’s shanties, Shabla Lighthouse, Bulgarian Black Sea Coast, 2014. Fuji X100, +1.4x, “50mm” tele-converter. Click to enlarge.

As a chill, gray autumn begins in Istanbul, I am warmed by recollections of the late-day glow of sunlight on the Black Sea coast at summer’s and of the fish that began to run last month and now run in even greater abundance; fish that pack local market stalls; glistening and oily, strong-tasting fish, their names shouted to passersby by fishmongers — diminutive, mackeral-like istavrit and far tinier anchovy-like hamsi; small,delicately-colored, bluefish-like çinekop, and meaty, sleek-skinned and red-gilled palamut (bonito). I’ll leave it to speakers of Turkish, Bulgarian, and Greek to argue over which languages the etymologies of these names belong to and — of far greater importance — which fish taste better grilled and which fried, which baked and which salted or cured.

Exuberance or Desperation? Street Vendor, Rear Wall of Egyptian Spice Market, Eminönü, Istanbul, Anno 2000

Street Vendor, Vicinity of Egyptian Spice Market, Eminönü, Istanbul; +/-2000; Rolleiflex Xenotar ƒ2.8, black/white negative. Click on image to enlarge.

In a late-day moment of exuberance — or might it have been desperation? — a teen-aged street vendor of shmattes (forgive me the Yiddish-ism) suddenly punctuates his sales shpiel by tossing part of his stock of clothing into the air. I caught the moment while working with a manually focusing twin-lens Rolleiflex and a handheld light meter — no mean feat if I might say so myself.

I took the photo almost 15 years ago. Where is the the street vendor today? I have no idea, although another generation of vendors still line the narrow street running behind the Misr Çarş (Egyptian Spice Market) in Eminönü, Istanbul. I do know, however, where his photo can be seen: Large prints thereof hang on the walls of (my only two!) “collectors” (close friends, actually) in Istanbul, one, in Çukurcuma, a talented emerging cinematographer, and the other, in Kuzguncuk, a corporate executive with an uncanny eye for photographic composition and emotionality. Both of these friends also share a visceral feeling for the pressures, uncertainties, and seeming absurdities of commerce at the street level. Both also know that — in our age of urban gentrification, rising income disparities, and hegemony of “big-box” retailing — the roles and presences of urban street vendors and the people they serve are being made increasingly marginal and becoming fated to near or full extinction.

A Tale of Urban Expansion: Late-19th-Century “Çarʂı” Row Houses, Functional Integration, Street-Life, and Class Mobility

Late-19th-century “çarșı”-style row house, Pirotska St., Sofia, Bulgaria, 2014. Note the neo-classical decorative elements and prim domesticity of the curtained windows on the second story and the presence of an Apteka (pharmacy) on the ground floor. (Fuji x100). Click on image to enlarge.

After the founding of an independent Bulgarian kingdom in the aftermath the Russo-Turkish War of the 1870s, the city of Sofia was chosen as the capital of the new nation-state. The choice of Sofia comprises a tale unto itself. True to the nation-state model, from day-one newly independent Bulgaria was giddy with dreams of expansion, northward, westward, and southward (to the east, expansion was blocked by the waters the Black Sea). Sofia, located near Bulgaria’s western border, would be at the country’s epicenter if Bulgaria would succeed in realizing its revanchist “manifest destiny” by expanding westward to the Lake Ohrid and annexing all of Macedonia.

At the time, Sofia had not fully recovered from a heavy earthquake and ensuing epidemics during the first quarter of the nineteenth century. The city boasted the palatial residence of the former Ottoman governor — soon to be re-purposed as the palace of a monarch recruited from a family of minor German “nobility”– and a main thoroughfare paved with ocher-colored bricks imported from abroad. For the rest, however, Sofia’s streets were warrens of winding lanes centered around Friday mosques, neighborhood mesjids for daily prayer, churches, wells and fountains.

The first step in creating a self-styled European capital was to sweep away the old Ottoman neighborhood structure and cut a street plan in the western model. The adopted plan combined a rectilinear street grid with a circular ring road and curving boulevards ala Hausmann’s plan for Paris. The next step was true to the model of mono-ethnic nation state that Bulgaria was striving to become: “ethnic cleansing. Gypsies and Jews, the latter comprising a full one-third of Sofia’s population of 10,000 at the time, were forcibly expelled from the city center; Jews to the newly cut parallel streets of Üç Bunar (“Three Wells)” to the west of downtown Sofia, and Gypsies further outward to the far bank of the Vladaya river, one of several seasonally flooding streams that together formed a moat surrounding the city.

Amongst the new grid of streets cut from Sofia’s main north-south boulevard through the old Ottoman quarter of Sungur and out to Üç Bunar was Pirot, today Pirotska. The downtown end of Pirotska eventually was lined with European-style apartment houses. At the Üç Bunar end of Pirotska an older form of architecture still dominates: Two-to-three-story row-houses built in çarʂı (Turkish for “arcade” and “market”) style, with commercial space for shops and craftsmen’s ateliers on the ground floors and family dwellings on the floor(s) above. Such çarʂı dwellings contributed to the re-shaping of Sofia by spatially integrating the functions of residential streets and market quarters. By doing so, they contributed to a culture of urban street life and the emergence of an urban middle- and lower-middle-class and paths to class mobility, both essential elements of democratic nation-building, an imperfect process in Bulgaria to this very day.

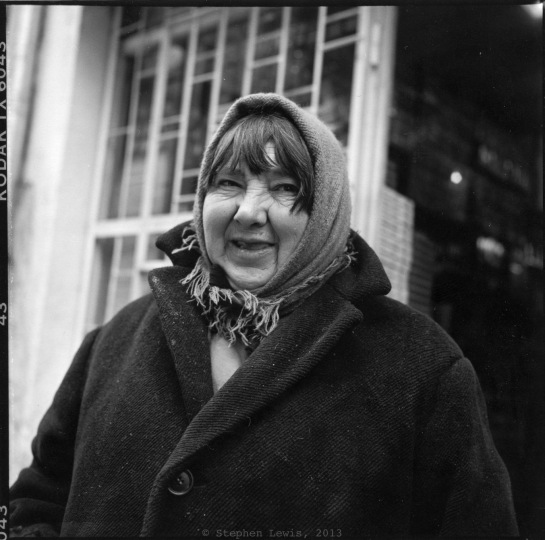

The Women’s Market, Sofia, Bulgaria, Mid-1990s: One Poem, Two Faces, and Recollections of Three Photographers

The late “Belleto,” cardboard and scrap paper scavenger, Women’s Market, Sofia, Bulgaria, winter 1997-8. (Rolleiflex Tessar f3.5, Tri-X 400 ASA, scan from print.) Click to enlarge.

Two informal portraits taken late one winter afternoon a decade and a half ago with an old Rolleiflex Tessar 75mm f3.5. For years after photographing in and around the outdoor “Women’s Market” in Sofia, Bulgaria, I found it difficult to photograph faces in Western Europe and even in my native New York. Faces in the latter locations appeared less marked by life and labor and more by fashion and pose. When looking at these two portraits anew after many years, I remembered phrase from a poem by the great Turkish poet Nazim Hikmet, something about “faces carved as if by plows.” A quick browse through the bookshelves and I tracked the words down to his passionate poem about the Virgin Mary and the faces and eyes of women, “The Faces of Our Women” (“Kadιnlarιmιzιn Yüzleri”).

The photos also reminded me of three photographers. The first is Austin, Texas based professional photographer and prolific writer and weblogger, Kirk Tuck, whose kind comments about the photo below in the course of an email exchange a year or so ago led to my relaunching Bubkes.Org.

The second is Pieter Vandermeer, a rough and tumble Rotterdam-based professional who, in the midst of his continuous flow of assignments, was the official photographer of the Rotterdam Film Festival in its initial years. Piet had learned photography in the Navy and not, like most Dutch photographers, at an art academy. Piet had the courage and integrity to look subjects (and clients!) in the eyes, engage them, and enable them to be themselves. Even when photographing people “on the street,” he would invariably track them down and present them with a print of their portrait, a confirmation of their and his person-hood. Piet’s approach was part of what prompts me every now and then to blow the dust off one my Rolleiflexes and set them to work. With a Rollei, I can lock eyes with a subject and, at the same time, compose, focus, and shoot. Because I am tall, the ability to use the Rollei at waist or chest level rather than eye level keeps me from looking down on subjects, literally and figuratively.

The third photographer is Elena Nenkova, a very fine Bulgarian studio and music event photographer who, back in the 1990’s, was also a printer of custom photographic enlargements. Many of the older photos I occasionally post on this site are scans of prints she made from my negatives. Thus, they are her work as well as mine and incorporate her vision, care, and excellence.

The Women’s Market, Sofia, Bulgaria: The Endurance of the 19th Century, Layers of Unwarranted Blame, and the Virtues of Slow Lenses

Roma broom sellers, Women’s Market, Sofia, Bulgaria, 1997. (Rolleiflex Tessar 𝘧3.5, Tri-X 400ASA, scan of print.) Click on image to enlarge.

Due to the length of this posting, I’ll invert the usual order and begin, rather than end, with a somewhat dry “footnote” on photographic technique; some reflections on the content of the photo — the Women’s Market, Sofia, Bulgaria — follow thereafter …

The Virtues of Slow Lenses

A good number of photographic sites I skim through on the internet betray an out-sized preoccupation with the virtues of fast, wide aperture lenses and their ability to create narrow planes of focus and patterns of background blur. As a counter to such, the photo above shows the virtues of slow, narrow-aperture lenses, in this case the 75mm Tessar f3.5, the built-in lens in a second-hand twin-lens Rolleiflex that I bought used more than three decades ago. The Tessar is one of the simplest designed and lightest weight lenses ever produced but when used properly it is second to none in sharpness, detail, and contrast. The Tessar’s 75mm focal length is a tad wider than 80mm, the usual “normal” focal length on 6x6cm medium-format film cameras. This 5mm difference enables the Tessar to deliver slightly wider coverage when used up-close, an advantage in environmental portraiture. The extra 5mm also provides a tad more depth of field and a slight exaggeration in perspective. The depth of field provided by the Tessar’s maximum aperture of f3.5 reduces the likeliness of focusing errors and keeps background details recognizable. In the photo above, thus, the main subject is in crisp focus while his wares and female colleague and the pedestrian traffic and architectural features of the market street behind him are sufficiently out of focus so as not to detract from the main subject but still clear enough to provide meaning and context.

Now, on to the subject at hand: the urban dynamics and historical tales the photo reveals …

The Women’s Market, Sofia, Bulgaria

The Women’s Market — located on broad curved street, following the course of a one-time riverbed, just west of the present-day center of Sofia, Bulgaria — has a history that stretches back to the centuries when what is now Bulgaria was part of the Ottoman Empire. Following Bulgaria’s independence from Ottoman rule in the aftermath of the Russo-Turkish War of the 1870s, the Women’s Market was Sofia’s main retail produce outlet. Nearly a century later, during the final years of the communist period, the Women’s Market provided a buffer of private enterprise and a reliable source of seasonal produce. Following the collapse of the Soviet bloc in 1989, the Women’s Market remained a chief source of fresh fruit and vegetables in a city in which old distribution systems had collapsed and new ones had not yet formed. Over the last decade, however, the Market has been in a state of decline. Supermarkets and shopping malls have taken root throughout Sofia, tastes have changed, and those of the city’s inhabitants with disposable cash and pretensions to mobility have moved from the urban core to the urban periphery taking their purchasing power with them.

In recent years, a large percentage of the Women’s Market’s street stalls have been removed by the municipality. At the moment, new modern multistory stall complexes wishfully described as being built for “tourists” and “artists” are under construction. What they will look like upon completion and the exact functions they will serve is anyone’s guess. What remains for now are rows of small enclosed kiosks selling local cheese, cured meats, and fish, plus scores of open fruit and vegetable stands under large brightly painted utilitarian canopies. Each stand is manned by vendors, some morose and silent, others vigorously or halfheartedly hawking their wares.

The endurance of the 19th century

In a lifetime of working in and observing cities in many places throughout the world, I’ve noticed that late-nineteenth century neighborhoods are amongst the last to be regenerated. This is due in part to the resilient endurance of their economic and social functions during the twentieth century and into the early-twenty-first. In such neighborhoods, cheap rents and high vacancy rates in storefront occupancy enabled the provision of inexpensive goods to those whose budgets constricted their choices.

The same interstice of factors offers opportunities for marginal entrepreneurship and a shot at mobility to those who might otherwise fall outside of the economy. The low profit-margins inherent to such entrepreneurship, however, can also make for dubious goods and equally dubious practices. Thus, shopping in the Women’s Market calls for a taste for sharp-tongued banter and a quick eye ever on the lookout for rigged scales and for good looking produce on display but underweight and damaged goods placed in one’s shopping bag. Still, where else can one buy, for example, persimmons or grapes, albeit on the last legs of their shelf-lives, for a third of the price of elsewhere and serviceable tomatoes for even far less?

Layers of unwarranted blame

There is a fine ethnic division of work and functions at the Women’s Market. Meat, cheese, and fish kiosks and stands offering wild herbs and mushrooms are run by ethnic Bulgarians. Fruit and vegetable stands and peripatetic bootleg cigarette operations are run by Roma (Gypsies). Storefronts in adjacent streets include honey and bee keeping supply stores run by Bulgarians and rows of “Arab” shops — halal butchers, spice stores, barbers, and low-cost international telephone services — run by and catering to increasing numbers of legal and illegal immigrants from Syria, Iraq, Palestine, Turkey, Central Asia, and Afghanistan. Many Bulgarians, their weak self esteem shakily bolstered by contempt for “others,” blame the shoddier commercial practices of this wonderfully vibrant marginal neighborhood on the presence and “inferiority” of such outsiders.

Several years ago, I attended an open town meeting on the future of the Women’s Market and its surroundings. The meeting degenerated into hysterical, racist tirades against the presence and practices of Roma stand-holders and market laborers, this despite their being hardworking people trying to extract a semblance of a living from admittedly marginal trade and low-value added labor. Banish the Gypsies, the sense of the meeting implied, keep the neighborhood “white” and Christian, and the market area with magically become upscale and all will be well. Not a thought was given to viewing the attempts at entrepreneurship on the part of Roma as social and economic assets to be incubated, this whether out of commitment to equal opportunity or to the insights of developmental economists such as Albert O. Hirschman. The neighborhood’s “Arabs” were denounced with equal rage.

Bulgarians complain that Roma do not work, but when Roma do work and commence to gain economic stability, the majority population reacts vengefully. Rage and blame have deep roots at the Women’s Market. On a symbolic level, blame even muddies the market’s name. During the communist period, the market had been renamed after Georgi Kirkov, an early Bulgarian left-wing trade unionist who died soon after the First World War. Following the collapse of Soviet-bloc communism, Kirkov’s name was expunged and Kirkov himself anachronistically assigned a share of blame for the mistakes and misdeeds of a neo-Stalist regime that came to power almost three decades after his death. Today, only a unkempt bust of Kirkov remains, mounted on graffiti-daubed pedestal in a small triangular park in which idle market day-laborers, elderly Roma mostly, congregate to smoke cigarettes, drink cheap alcohol from half-pint bottles, and while away the hours.

Festering blame that has never been resolved

There is another level of blame and contempt, however, that festers under the surface of debates pertaining to the Market. During the Second World War, the Bulgarian army rounded-up and deported to their death 18,000 Jews from Macedonia and northeastern Greece, areas ceded to Bulgaria by Nazi Germany in reward for favorable trade terms and a lion’s share of Bulgaria’s gold reserves. At the same time, within the boundaries of the Kingdom of Bulgaria proper, 50,000+ Jews were socially and economically disenfranchised and legally robbed of their real and movable property. Tens of thousands of Jews were deported from Sofia to the countryside; the younger and fitter male deportees were sent to work as slave laborers on road crews and the rest were left to fend for themselves without means of support in isolated villages. As a boon to ethnic Bulgarians living in Sofia, the deportation freed up hundreds of businesses (most of them marginal), thousands of dwellings in a city short of housing stock, and tens of thousands of places in the workforce.

From the post-war period on, Bulgarians called the seizure of Jewish property and the deportation of Jews from Sofia “The Saving of the Jews,” giving a self-congratulatory spin to the large percentage of Jews in Bulgaria that came through the war alive, something that can be more accurately ascribed to Bulgaria’s being knocked out of the war by the Soviet Union in mid-1944. The reaction of more than 90% of the Jews in the Bulgaria to such a “saving,” was clear enough: emigrate en masse, mostly to Israel, not long after the war ended. Prior to the war, Sofia’s Jews had formed the bulk of the residents of the market quarter. Their deportation and post-war emigration created a vacuum in the midst of the city’s center and led to discontinuities and dislocations from which the streets surrounding the Women’s Market have yet to recover.

Rag-sellers, “çıfıtcı,” and voting with my wallet

Today, in a country almost without Jews, Jews remain an obsession for many Bulgarians and a target of their hostility and condescension. This especially holds true for populist agitators and amongst Bulgarians with higher incomes and social standing, whether real or self-ascribed. In such circles, Jews are blamed for communism and for capitalism and for imagined secret cabals that subvert Bulgaria and steer the world. The poisonous, fraudulent “Protocols of the Elders of Zion” remains a best-seller at outdoor book stalls in Sofia, as do conspiracy theory books involving Israel’s Mossad. Walls are daubed with antisemitic (and anti-Roma and anti-Turkish) slogans, the work of bands of neo-fascist football (soccer) supporters. Few social gatherings of upper-income or self-styledly cultured Bulgarians are complete without the telling of “yevreiski vitsovi” (“Jewish jokes”) — jokes about Jews rather than by them, usually with story lines about rich but stupid Jews outsmarting themselves in avaricious schemes.

In truth, prior to the Second World War, most Jews in Bulgaria were marginal shopkeepers and low-income craftsmen, laborers, and peddlers. Like today’s Roma, Jews were blamed for the inherent defects of the economic niches in which they labored and the social niches in which they lived. Early in the twentieth century, many Sofia Jews were old-clothes and rag vendors, literally, thus, members of the “lumpenproletariat.” To this day, in Bulgaria, Jews — be they doctors, scholars, merchants, or ordinary folks like this writer — are contemptuously referred to as “chifuti,” a Bulgarian-language bastardization of the Turkish term “çıfıtcı” or old-clothes- and rag-seller. Personally, as someone who has worked for others since my 13th year, and whose roots are in a world not dissimilar to the that of the Women’s Market, I am quite willing to wear the label of “çıfıtcı“with pride. For this reason, when in Sofia, I happily continue to do my shopping in and around the Women’s Market and loyally patronize its Roma vendors … this regardless of any and all bruised and overripe fruit or real or imagined thumbs on scales! As to antisemitic, anti-Roma , anti-worker “cultured” Bulgarians, as we used to say in the Yiddish-English patois of my native Lower East Side of Manhattan: “Geh’n’d’r’ert!” (“Sink into the ground”). After years of listening to their racist hatefulness and class-condescension of , I’m always available to lend a helpful push.

Ghost of Commerce Past: Abandoned Storefront, Tahtakale Quarter, Eminönü, Istanbul

Former storefront, ground-floor of an abandoned late19th-century Greek-style apartment house, Tahtakale quarter, Eminönü, Istanbul, 2012. (Fuji X100). Click to enlarge.

A boarded-up storefront in a boarded-up building, a ghostly survivor in a once-thriving neighborhood. The brick façade of the ground floor and wood-plank-covered exterior of the upper floors suggest that the building may have been built and owned by Istanbul Greeks a century to a century-and-a-half ago.

Mattresses, Brooms, and Art in Bulk, Tahtakale, Istanbul: Street Commerce Direct and Unadorned

Exit Istanbul’s famed Egyptian Spice Market in the direction of the mosque of Rüstem Paşa and the neighborhood of Tahtakale and one passes through a narrow street filled with slow moving crowds of tourists and local shoppers from throughout the city. The first few hundred meters of the street is lined with scores of shops selling fresh ground coffee, nuts and dried fruit, followed by stalls and workshops stocked with traditional wooden and metal kitchenware and folding tables, baskets, and other accoutrements de rigueur for street vendors. Continue further in the direction of Unkapani and the crowds thin out and the goods in the shops and stalls become more prosaic and spartan, necessities geared to the mundane needs of low income shoppers from the immediate surroundings. Artifice is absent, goods are displayed matter-of-factly — neither display windows nor vicarious seduction, no hawkers, just commerce at its most direct and unadorned.

Left: The wares of a broom seller with façade painted to match. Right: Affordable art. Tahtakale, Eminönü, Istanbul, 2012. (Fuji X100). Click to enlarge.